Kolmogorov Complexity

In the previous chapter, we saw what entropy tells us about compressing strings. If we treat letters independently, coding theory is especially powerful. But that's an assumption that good compression algorithms can't make.

Kolmogorov complexity is the ultimate limit for how much a file can be compressed. This makes it a very powerful theoretical concept to have in our dictionary!

Kolmogorov complexity of an object is the length of its shortest specification. This is the ultimate limit of compression.

The Mandelbrot Set

Take a good look at the following picture.1 It shows a so called Mandelbrot set -- we color each pixel of the plane based on how quickly a certain sequence of numbers shoots to infinity.

If you take print screen of this picture and save it on your disk, it's going to take a few MB. But what if you instead save the instruction for how to create this image? All relevant ingredients are stored in the two boxes below the picture - the formula used to create it, and the coordinates of the plane you are looking at. We are talking about less than kilobyte of memory now.

This is the gist of Kolmogorov complexity. For any given object - say, represented as a binary string - it's Kolmogorov complexity is the length of the shortest program that prints that string.

Here are a few more examples.

- Although digits of have many random-like properties, the Kolmogorov complexity of its first million digits is extremely small. That's because there are some extremely short programs printing it.

- Larger numbers (written down in binary) typically have larger Kolmogorov complexity. But there are huge numbers like with very small Kolmogorov complexity.

- Whenever you can ZIP a file to a size of 100MB, you can say that "Kolmogorov complexity of the file is at most 100MB"

- The Hutter's challenge from coding theory chapter is about estimating the Kolmogorov complexity of 1GB of Wikipedia

- If you keep flipping a coin times, the resulting sequence is likely to have Kolmogorov complexity of about . There's no good way of compressing it.

Choosing the language

There is an awkward problem with the definition of Kolmogorov complexity. It's the length of the shortest program -- but what programming language do we use? Python? C? Assembly? Turing machine? Do we allow languages and libraries? Printing million digits of can then reduce to this:

import sympy

print(sympy.N(sympy.pi, 1000000))

The important insight is that, at least if we stay on the theoretical side of things, the choice does not matter that much. The trick is that in any (Turing-complete) programming language, we can build an interpreter of any other programming language. Interpreter is a piece of code that reads a code written in some other language, and executes its instructions.

In any reasonable programming language, you can write an interpreter for any other reasonable language in at most, say, 1MB. But this means that Kolmogorov complexity of any object is fixed 'up to 1MB': If you have a 100MB Python script that prints the file, then you have a 101MB C, Assembly, Java, ... script printing the same file - just write a code where the first 1MB is an interpreter of Python tasked to execute the remaining 100MB.

So for large objects (like the 1GB Wikipedia file from Hutter's prize), there's nothing awkward in using Kolmogorov complexity. The flip side is that it's pretty meaningless to argue whether the Kolmogorov complexity of is 200 or 300 bytes. That difference depends on the choice of programming language too much.

Kolmogorov vs entropy:

Both Kolmogorov complexity and entropy are trying to measure something very similar: complexity, information, compression limit. Naturally, there are closely connected. The connection goes like this: If you have a reasonable distribution () over bit strings and you sample from it (), then the entropy of the distribution is roughly equal to the expected Kolmogorov complexity of the sample. I.e., .

Let's see why this is true on an example. Take a sequence of fair coin flips. This is a uniform distribution over binary strings of length . The entropy of this distribution is . Now let's examine the Kolmogorov complexity.

On one hand, the Kolmogorov complexity of any -bit string is at most

That's because in any (reasonable) language, you can just print the string:print('01000...010110')

But can the average Kolmogorov complexity be much smaller than ? Notice that our uniform distribution contains many strings with very small Kolmogorov complexity, like the string . The reason why those special snowflakes don't really matter on average is coding theory. We can construct a concrete code like this: for any string in our distribution, its code name is the shortest program that prints it.2 The average length of this code is exactly . But we have seen that any code has its average length at least as big as the entropy. Hence, and we have the formula:

If you look at above proof sketch, you can notice that we did not really use that the distribution is uniform, it works pretty much for any distribution.3

However, the case of a uniform distribution is the most interesting: It tells us that most -bit strings can't really be compressed, since their Kolmogorov complexity is close to ! In fact, -bit strings with Kolmogorov complexity are called Kolmogorov random, to highlight the insight that bits are random if we can't compress them.

Prediction, compression, and the Chinese room

In previous chapter, we talked about how prediction and compression are closely related. It may have looked a bit like some kind of algebraic trick - coincidentally, surprise is measured as and lengths of good code name is also , so there's the connection between prediction and coding. Kolmogorov complexity gives a smooth language to talk about this connection. In particular, I find it especially helpful that we can talk about compression / Kolmogorov complexity without talking about probability distributions.

Let's say we want to discuss how LLMs are "good at predicting the next token on Wikipedia" and make it more mathematically precise. Using the language of cross-entropy and entropy is a bit awkward - it has to involve some kind of distribution over inputs. We have to imagine some kind of abstruse probability distribution over thoughts about the world written in English. Then, let be the distribution over texts generated by running our LLM. The technical sense in which the LLM "is good at predicting" is that is small.

Using the language of compression, we can reformulate "being good at predicting Wikipedia" as "being good at compressing Wikipedia". For me, this is much more tangible! LLMs are simply smart enough not to find "Wikipedia" that surprising - as measured in bits that we have to store so that the LLM can recover the original text from them. This story about what's happening in LLMs does not require arguing about any distribution over all English texts.

Here's a concrete example that helps illustrate these concepts. A philosopher called John Searle once proposed a thought experiment called Chinese room.

Let me quickly explain the gist. 4 If you are from the older generation like me, you might remember that pre-2022, there was a thing called Turing test:5 Imagine that you can chat for a few minutes with an entity that is either a human, or an AI impersonating a human. If you can't reliably tell the two cases apart, Turing claims that we should concede that the AI is intelligent.

But Searle objects: What if the AI was just a long list of rules? (In his experiment, he imagines a person locked in a room with a Chinese conversation rulebook) This was actually how some pre-deep learning AIs faked their way through short (5 minutes) Turing test games. The AIs were just an incredibly long lists of pattern matching rules like "If they seem to ask you about your favorite artist, tell them Madonna and ask them about their favorite artist. " This works for very short conversations, since it was relatively predictable what kind of questions the human judges are typically asking.

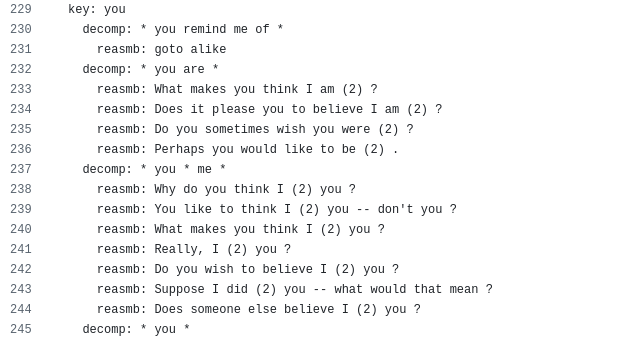

Pre-deep-learning chatbots like ELIZA are mostly just lists of common phrases, especially questions that pretend to be relevant. If you keep adding IFs and ELSEs, you get better models of human language. But there's no compression happenning, so the chatbot does not really generalize to new situations.

The problem with this approach is that it gets exponentially harder - for each additional minute of the immitation game, the number of rules included in the intelligence fakers has to grow by a multiplicative factor. That's because there is no compression happening in those programs - they were not trying to predict what happens in human-like conversations, they were just trying to list all of them. Thus, such programs never really generalized, they did not lead to new, interesting insights. And, Searle has a very good point that even if the programs can fool people on Turing test for a few minutes, there is not really much of an understanding happening.

This is of course very different for current AIs. As we now understand, they are literally trained to predict human conversations and writings. Or, equivalently, they are trying to compress them. This compression is the crucial difference from the earlier Turing-test-fakers. The architects of current AI like Ilya Sutskever understand this difference extremely well and it was the reason why they were optimistic about the overall approach of training general intelligence by modelling text. They understood that being good on the "simplistic" task of predicting the next token does not only force you to learn English words (GPT-1) or the basic grammar of a couple of languages (GPT-2). To get really good at predicting the next token, you have to understand the underlying reality that led to the creation of that token. Understanding reality partially consists of learning facts, but more importantly, it requires intelligence to combine them. 6

Solomonoff prior & induction

What's the most natural distribution over all (finite) binary strings, if what we care about is their Kolmogorov complexity? The maximum entropy principle says we should consider the distribution , for some . In a minute, we will see that the right is such that 7 This distribution is called Solomonoff prior. 8

It's called prior because this is how we typically want to use this distribution. Similarly to other maximum entropy distributions, this is where should start before we start making observations and updating it. I find it philosophically very appealing, feel free to check the expand boxes.